Red Scare

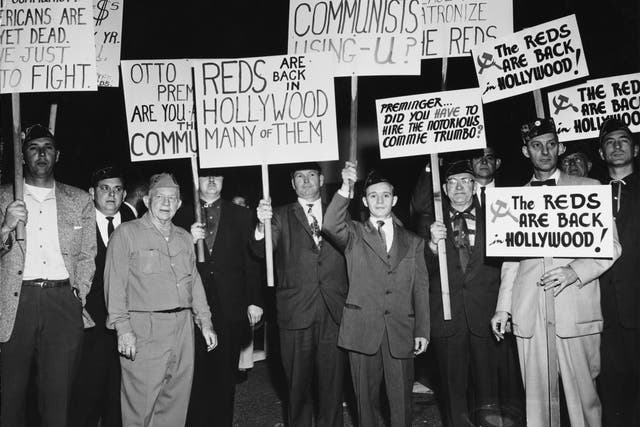

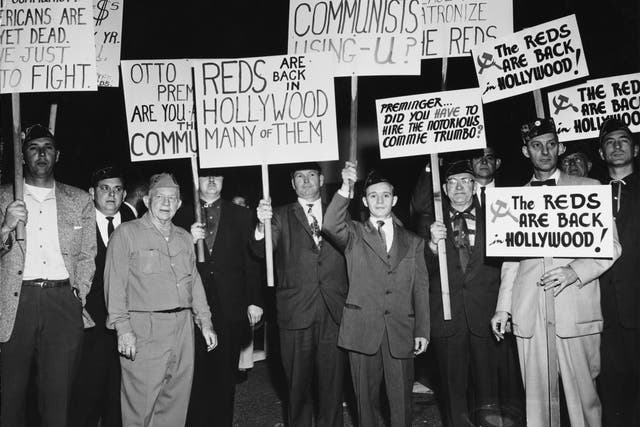

placards against Communist sympathizers outside the Fox Wilshire Theatre in occasion of the premiere of film 'Exodus', which marked the end of the 'Hollywood Blacklist' when screen player Dalton Trumbo, a Communist Party member from 1943 to 1948 and member of the Hollywood Ten, was credited as the screenwriter of the film, Beverly Hills, Los Angeles, California, US, December 1960. (Photo by American Stock Archive/Archive Photos/Getty Images)" width="" height="" />

placards against Communist sympathizers outside the Fox Wilshire Theatre in occasion of the premiere of film 'Exodus', which marked the end of the 'Hollywood Blacklist' when screen player Dalton Trumbo, a Communist Party member from 1943 to 1948 and member of the Hollywood Ten, was credited as the screenwriter of the film, Beverly Hills, Los Angeles, California, US, December 1960. (Photo by American Stock Archive/Archive Photos/Getty Images)" width="" height="" />

The Red Scare was hysteria over the perceived threat posed by Communists in the U.S. during the Cold War between the Soviet Union and the United States, which intensified in the late 1940s and early 1950s. (Communists were often referred to as “Reds” for their allegiance to the red Soviet flag.) The Red Scare led to a range of actions that had a profound and enduring effect on U.S. government and society. Federal employees were analyzed to determine whether they were sufficiently loyal to the government, and the House Un-American Activities Committee, as well as U.S. Senator Joseph R. McCarthy, investigated allegations of subversive elements in the government and the Hollywood film industry. The climate of fear and repression linked to the Red Scare finally began to ease by the late 1950s.

First Red Scare: 1917-1920

The first Red Scare occurred in the wake of World War I. The Russian Revolution of 1917 saw the Bolsheviks, led by Vladimir Lenin, topple the Romanov dynasty, kicking off the rise of the communist party and inspiring international fear of Bolsheviks and anarchists.

In the United States, labor strikes were on the rise, and the press sensationalized them as being caused by immigrants bent on bringing down the American way of life. The Sedition Act of 1918 targeted people who criticized the government, monitoring radicals and labor union leaders with the threat of deportation.

The fear turned to violence with the 1919 anarchist bombings, a series of bombs targeting law enforcement and government officials. Bombs went off in a wide number of cities including Boston, Cleveland, Philadelphia, D.C., and New York City.

The first Red Scare climaxed in 1919 and 1920, when United States Attorney General Alexander Mitchell Palmer ordered the Palmer raids, a series of violent law-enforcement raids targeting leftist radicals and anarchists. They kicked off a period of unrest that became known as the “Red Summer.”

Cold War Concerns About Communism

Following World War II (1939-45), the democratic United States and the communist Soviet Union became engaged in a series of largely political and economic clashes known as the Cold War. The intense rivalry between the two superpowers raised concerns in the United States that Communists and leftist sympathizers inside America might actively work as Soviet spies and pose a threat to U.S. security.

Who Were the Hollywood 10?

Hollywood blacklisted these screenwriters, producers and directors for refusing to testify before the House Un‑American Activities Committee.

Why the Rosenbergs’ Sons Eventually Admitted Their Father Was a Spy

Michael and Robert Rosenberg became orphans when their notorious parents were executed for espionage. Then what happened?

How Communists Became a Scapegoat for the Red Summer ‘Race Riots’ of 1919

A conspiracy theory emerged during the Red Scare, blaming “the Bolsheviki” for protests and violence.

Hysteria and Growing Conservatism

Public concerns about communism were heightened by international events. In 1949, the Soviet Union successfully tested a nuclear bomb and communist forces led by Mao Zedong (1893-1976) took control of China. The following year saw the start of the Korean War (1950-53), which engaged U.S. troops in combat against the communist-supported forces of North Korea. The advances of communism around the world convinced many U.S. citizens that there was a real danger of “Reds” taking over their own country. Figures such as McCarthy and Hoover fanned the flames of fear by wildly exaggerating that possibility.

HISTORY Vault: The Korean War: Fire & Ice

As the Red Scare intensified, its political climate turned increasingly conservative. Elected officials from both major parties sought to portray themselves as staunch anticommunists, and few people dared to criticize the questionable tactics used to persecute suspected radicals. Membership in leftist groups dropped as it became clear that such associations could lead to serious consequences, and dissenting voices from the left side of the political spectrum fell silent on a range of important issues. In judicial affairs, for example, support for free speech and other civil liberties eroded significantly. This trend was symbolized by the 1951 U.S. Supreme Court ruling in Dennis v. United States, which said that the free-speech rights of accused Communists could be restricted because their actions presented a clear and present danger to the government.

Red Scare Impact

Americans also felt the effects of the Red Scare on a personal level, and thousands of alleged communist sympathizers saw their lives disrupted. They were hounded by law enforcement, alienated from friends and family and fired from their jobs. While a small number of the accused may have been aspiring revolutionaries, most others were the victims of false allegations or had done nothing more than exercise their democratic right to join a political party.

Though the climate of fear and repression began to ease in the late 1950s, the Red Scare has continued to influence political debate in the decades since. It is often cited as an example of how unfounded fears can compromise civil liberties.

HISTORY.com works with a wide range of writers and editors to create accurate and informative content. All articles are regularly reviewed and updated by the HISTORY.com team. Articles with the “HISTORY.com Editors” byline have been written or edited by the HISTORY.com editors, including Amanda Onion, Missy Sullivan, Matt Mullen and Christian Zapata.

placards against Communist sympathizers outside the Fox Wilshire Theatre in occasion of the premiere of film 'Exodus', which marked the end of the 'Hollywood Blacklist' when screen player Dalton Trumbo, a Communist Party member from 1943 to 1948 and member of the Hollywood Ten, was credited as the screenwriter of the film, Beverly Hills, Los Angeles, California, US, December 1960. (Photo by American Stock Archive/Archive Photos/Getty Images)" width="" height="" />

placards against Communist sympathizers outside the Fox Wilshire Theatre in occasion of the premiere of film 'Exodus', which marked the end of the 'Hollywood Blacklist' when screen player Dalton Trumbo, a Communist Party member from 1943 to 1948 and member of the Hollywood Ten, was credited as the screenwriter of the film, Beverly Hills, Los Angeles, California, US, December 1960. (Photo by American Stock Archive/Archive Photos/Getty Images)" width="" height="" />